NEXT UP

Gastrointestinal Allergies

01

Eosinophilic Esophagitis

(esophagitis) (EoE)

Description.

Eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) is the most frequent eosinophilic gastrointestinal disorder, and is characterized by i) esophageal symptoms including feeding intolerance, gastro-esophageal reflux disease (GERD), dysphagia and food impaction, and ii) an eosinophil predominant inflammation of ≥15 eosinophils per high power field (HPF; standard size of ∼0.3 mm2) in the esophageal tissue after exclusion of other disorders associated with similar clinical histologic, or endoscopic features.2,3 It has also been described as a “food antigen-mediated disease”.4 Food allergy (FA)-associated EoE is commonly associated with 6 foods, namely cow’s milk, wheat, soy, egg, nuts, and fish4 but can vary by region and between individuals.

Prevalence.

The prevalence of EoE has greatly increased over the past 2 decades, in part due to increased awareness and improved disease detection.5 Data from the United States (US), in 2018, reported the overall prevalence to be 68 per 100,000 (~0.68/1000) children <10 years of age, ranging from 115–123 per 100,000 (~1/1000) children and adolescents (10–19 years).5

In a pooled analysis of 14 studies, both adults & children, in North America and Europe, the overall prevalence of EoE in children was proposed to be 34.4 cases/100,000 (0.34/1000).6 However, according to other more recent studies in Spain, the prevalence was somewhat higher at 53.4 cases/100,000 (0.54/1000).6 Furthermore, EoE appears to be consistently higher in males compared to females, across all age groups.5-7

Dietary Management.

In patients with symptomatic EoE, Proton Pump Inhibitors (PPIs), ingested topical glucocorticosteroids and the elimination diet are effective in inducing histological and clinical remission.7,8 A 6-food elimination diet is preferable to a 2 or 4 food elimination diet but is associated with lower compliance and increased number of endoscopies.7 A step-up approach has also been advocated, starting with the most commonly implicated 2 foods i.e., cow’s milk and wheat/gluten (the 2-food elimination diet (2 FED)); and in those that fail the 2 FED a 4 FED is initiated and so on to the 6 FED.9 In this study >40% of children achieved remission on the 2 FED, 60% with the 4 FED and 79% with the 6 FED.9

Historically the elemental diet was sometimes used due to its efficacy, but today it has a limited role to play in managing EoE due to poor compliance.7 It is advised that these diets be therefore reserved (only) for children with refractory EoE when conventional treatments have failed.7 Meanwhile allergy testing to foods (eg, skin prick, specific IgE and patch testing) is not recommended as a method for choosing which foods to restrict.7 Once the therapy has been initiated (dietary or pharmacological), then an endoscopy with biopsy is usually performed while on the therapy - as symptoms may not always correlate with histological activity.7 Endoscopic procedures like dilation may be considered in some (severe) cases with fibrostenotic disease.7

02

Food Protein-Induced

Enterocolitis Syndrome

(FPIES)

Description.

FPIES is a non–IgE-mediated food allergy that typically presents in infancy, with repetitive protracted vomiting.10,11 It has been reported that in cases of acute FPIES, vomiting begins approximately 1 to 4 hours after food ingestion, often accompanied by lethargy and pallor.10,11 Furthermore, watery diarrhea (occasionally with blood and mucous) has been reported within 5 to 10 hours after ingestion of the implicated food lasting for up to 24 hours.10,11 A concerning potential side-effect of acute FPIES is dehydration, which can lead to hypotension and shock when severe.10,11 However, symptoms of acute FPIES usually resolve within 24 hours and most children with acute FPIES, are well between episodes with normal growth.10,11

Chronic FPIES is most often seen in infants younger than 4 months on cow’s milk (CM) or soya formula, where the offending food is regularly and repeatedly ingested.10,11 Symptoms present as chronic/intermittent emesis, watery diarrhea, hypoalbuminemia and faltering growth.10,11. Upon elimination of the food triggers, symptoms resolve, but subsequent feeding (accidental exposure or oral food challenge) can induce an acute FPIES episode within 1 to 4 hours of food ingestion.10,11

Cow’s Milk (CM) appears to be the most commonly implicated liquid food in FPIES – with 58% reacting to CM on oral food challenge (OFC) in one study.12 While a combination of soy and CM appear to be commonly linked to FPIES in the US (25% to 50% reported) as well as rice and oats.10 In general, the most commonly reported casual foods are milk and soy for liquid foods and grains (rice, oat) as solid foods.11 However, in the majority of children (65%) FPIES seems to be caused by a single food.13

Prevalence.

The cumulative incidence estimated in the United States, Israel, Australia, and Spain range from 15 to 700 cases/100,000 (0.15-7/1000).14 A population-based survey in the US reported an estimated lifetime prevalence of 510 cases /100,000 (~5/1000) in <18 years and 220 cases/100,000 (~2/1000) in adults.15 In Western countries, the childhood prevalence of FPIES to cow's milk was reported to 340 cases/100,000 (~3/1000).16

Dietary Management.

Acute FPIES is managed according to the severity in the individual child; milder reactions can resolve with oral rehydration, whereas moderate to severe reactions require more aggressive actions including fluid resuscitation (with repeated boluses).11 Long-term management of FPIES includes avoidance of the trigger food(s), dietary and nutritional monitoring, treatment of reactions in case of accidental ingestion or new trigger foods, and re-evaluation for resolution.11 For infants with cow’s milk or soy related FPIES, breastfeeding or use of an extensively hydrolysed formula (eHF) is encouraged.11 International FPIES guidelines do not recommend routine allergen avoidance in breastfeeding mothers unless the child presents with symptoms whilst breastfeeding (which is rare).16 Most infants will tolerate an eHF, however, 10–20% may require an amino acid-based formula (AAF).10,11 In FPIES, overall remission rates range widely from 50 to 90% by the age of 6 years, and the timing of remission appears to be dependent on both the implicated food and the population studied.13 Tolerance to cow’s milk and soy is typically achieved earlier than to grains or other solid foods.11

03

Food Protein-Induced

Enteropathy (FPE)

Description.

Food protein-induced enteropathy (sometimes referred to as cow’s milk-sensitive enteropathy) is an uncommon syndrome of small-bowel injury with resulting malabsorption.13 Features of FPE include non-bloody diarrhea, malabsorption, protein-losing enteropathy, hypoalbuminemia, and failure to thrive.13 It is also characterized by abnormal small intestinal mucosa and chronic gastrointestinal symptoms while food is being regularly ingested.13 FPE typically starts in the first months of life, usually within weeks after the introduction of cow’s milk (CM) formula, and presents as recurrent vomiting, (non-bloody) diarrhea, malabsorption, faltering growth, abdominal distention, and hypoalbuminemia.17-19 Cow’s milk and soya are commonly implicated, however other food proteins, such as wheat, and egg, have also been reported.13,18,19 FPE can be difficult to differentiate from some forms of FPIES; although it lacks both the acute symptoms seen in the FPIES, and the severe dehydration and metabolic acidosis seen in chronic FPIES.18

Prevalence.

In a population-based Finnish study, the prevalence of FPE to cow’s milk in older children was 2200 cases/100,000 (~22/1000).20 Although the overall prevalence of FPE is unknown, reports suggest that the prevalence of this non-IgE-mediated food hypersensitivity syndrome has been declining over the last few decades.13,18,19 Potential explanations for the decline in prevalence of FPE includes the upsurge in breastfeeding practices, which may be protective, and the use of better adapted formulas with a lower protein content.18,19

Dietary Management.

The cornerstone of the management of FPE is avoidance of the offending food(s). In children with FPE, symptoms usually resolve within 1–4 weeks of elimination of the offending food, although mucosal repair with normalization of disaccharidase activity may take up to 18 months to improve.13 In formula-fed infants guidelines recommend an eHF as the first-line option, particularly in infants under 6 months of age, and with evidence of failure to thrive. When the eHF is not tolerated or if the child’s initial trigger is an eHF, an AAF is recommended.13 If cow’s milk avoidance does not improve the symptoms, other food elimination trials (e.g., soy, egg, wheat) may be indicated, sequentially.18

04

Food Protein-Induced

Allergic Proctocolitis (FPIAP)

Description.

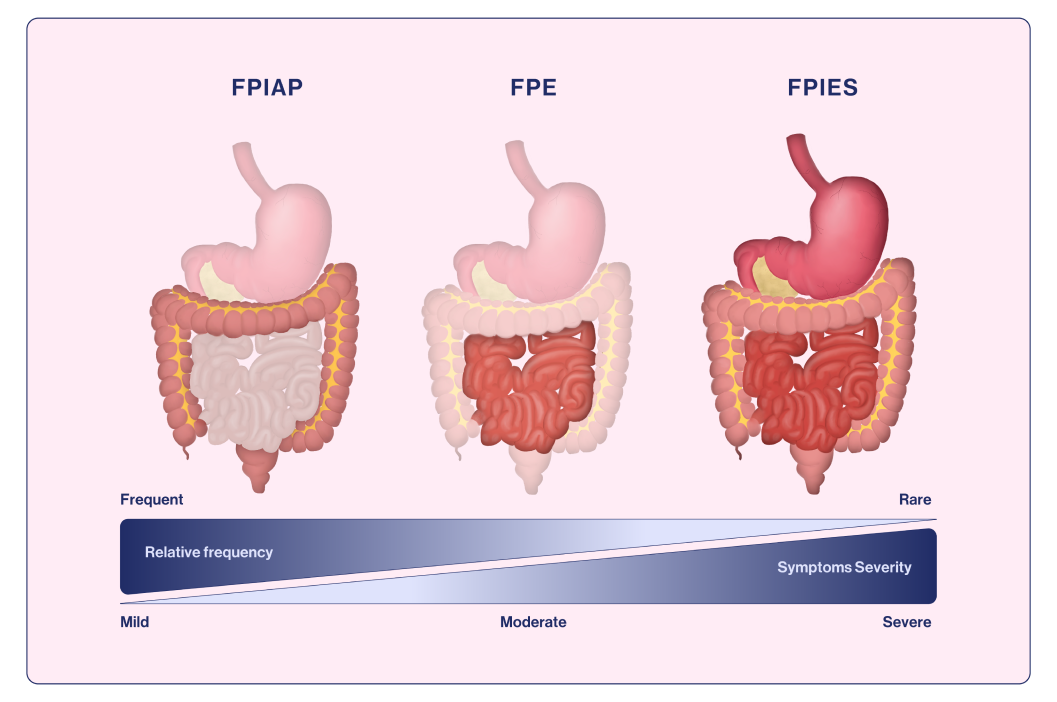

FPIAP is considered the most benign form of non-IgE mediated food allergy, that is characterized by blood and sometimes mucous in the stools of otherwise healthy, normally growing infants.18 It affects infants <12 months of age and typically appears between 2 and 8 weeks of life. The onset of symptoms may be acute (<12 hours after exposure) but is often more sinister, with a gradual increase in symptoms as the food protein is introduced.18 FPIAP symptomatology is seen as localized inflammation of the distal colon, causing hematochezia (blood in stools) in otherwise well-appearing infants19 (Figure 1). It has been suggested to occur in up to 60% of breastfed infants.21 Cow’s milk is the most frequent trigger in FPIAP (similar to FPIES and FPE) but soy is also implicated.19,21

Prevalence.

Of the non-IgE gastrointestinal food allergies, FPIAP is the most frequent, although the exact prevalence is not well established.19 A large study of an Israeli birth cohort found the overall prevalence of FPIAP to be relatively low, at 160 cases/100,000 (1.6/1000).22 In infants with rectal bleeding, FPIAP has been found to be the cause in 18 - 64% of cases.23,24

Dietary Management.

The vast majority of exclusively breastfed infants with FPIAP will respond to the maternal elimination of all milk products, however occasionally, the elimination of multiple foods may be required, commonly soy, egg and/or wheat.16,19,21 Recent European guidelines recommend a 2–4 weeks maternal elimination diet, followed by an attempt to re-introduce foods in order to confirm the diagnosis.16 When the maternal restriction diet is unsuccessful or for those who are not exclusively breastfed, an extensive hydrolysate can be trialed. However, when hematochezia persists then an amino acid-based formula is indicated.19,21 Soy formula may induce bleeding in a subset of infants reacting to cow’s milk (CM), so soy is also commonly eliminated along with CM, at least for the diagnostic period of the elimination diet.21

Figure 1. Gastrointestinal organs affected in the different non-IgE -mediated gastrointestinal food allergies.

Adapted from Labrosse et al., 202019

05

Allergic Dysmotility

Disorders

Description.

Gastro-esophageal reflux (GER) is defined as the passage of any gastric contents into the esophagus which occurs in early childhood and may lead to regurgitation and intermittent vomiting.25 When GER leads to troublesome symptoms it is referred to as GER disease (GERD).25 The typical GI symptoms attributed to GERD are recurrent regurgitation and vomiting in infants, with or without excessive crying, distress/discomfort/irritability, dystonic neck posturing, feeding difficulties and food refusal, faltering growth and esophagitis. In older children, symptoms can also include chest and epigastric pain and dysphagia.25

The mechanisms behind GERD are multiple, but the predominant mechanism is attributed to transient lower esophageal sphincter (LOS) relaxation. Both IgE-mediated, non-IgE-mediated or mixed IgE/non-IgE-mediated food allergy (FA) (including CMPA) have been implicated in the pathophysiology of GERD.25 Food Allergy (FA)-associated GERD, primarily non-IgE mediated FA, has been described in young children, with the majority presenting within the first 6 months of life, with food aversion and faltering growth.25

The relationship between FA and GERD is likely to be bidirectional, with GERD inducing changes in mucosal immunity that may in turn increase the risk of FA, and FA-related symptoms that are manifestations of digestive dysmotility which may be due to food allergen-induced mediators.25

Prevalence.

A number of studies have examined the presence of cow’s milk protein allergy (CMPA) in infants with symptoms attributable to GERD. In some smaller older studies CMPA-associated GERD was reported to range from 16–56%26-29 but a more recent review concluded that the real prevalence between CMPA and GERD remains unclear.30

Dietary Management.

The most common allergen reported in FA-associated GERD is cow's milk according to the recent EAACI position paper.25 The first step is the diagnostic process is taking a detailed clinical history, assessment of growth and feeding history (including any dietary changes associated with worsening of symptoms) and determining whether other atopic features are present25 (Figure 2). A positive family history of atopy and early onset eczema should also be established which may increase the risk of the child having an allergic disease.25 Once CMPA-associated GERD has been established experts propose to consider a cow's milk elimination diet prior to the use of medications in (non-breastfed) infants.31 In the EAACI position paper they suggested a minimum of 2 weeks on the elimination diet is needed before symptoms will start to improve.25 However, it can take up to 6 weeks in some cases, which should then be followed by the reintroduction of the allergen (offered daily in age-appropriate portions for around 2 weeks).25 Elimination of cow’s milk/dairy from the infant diet has been shown to significantly reduce esophageal acid exposure and clearance, suggesting improved esophageal peristaltic function.32

Breastfeeding should be supported in infants with GERD and a maternal elimination diet should only be considered if the child presents with symptoms whilst breastfeeding.25 When breastmilk is not available, or the child is not exclusively breastfed, then an extensively hydrolyzed formula (eHF) is recommended as the first choice. However, EAACI proposed that when the infant has faltering growth, multi-system involvement or when multiple foods are suspected then an amino acid-based formula (AAF) may be considered.25 They also indicated that thickened eHF or AAF may offer some additional benefits in infants with ongoing gastrointestinal symptoms.25

The EAACI position also proposed that if symptoms do not fully improve (e.g., on the CM-free diet) and other ongoing lower GI symptoms exist that might be related to non-IgE mediated FA and/or atopic dermatitis, then further food eliminations may need to be considered (i.e., soya, egg and wheat).25

After 6–12 months of food elimination (when confirmed food allergy-related GERD) a trial of the offending allergens should be initiated according to the EAACI experts.25

EAACI proposed that proton-pump inhibitors (PPI) may be used for toddlers and school aged children with FA-associated GERD, meanwhile in infants (< 1year of age) pharmacological treatments should only be considered after an elimination diet has failed.25

Figure 2. EAACI position paper proposed pathway for the diagnosis and management of FA-associated GERD.

Adapted from Meyer et al., 202225